Of all distributed energy resources (DERs), electric vehicles (EVs) may be the most transformative. While rooftop solar, often paired with batteries, is decentralizing the energy system, EVs are turning the entire energy transition on its head. More than just a green option for those who can afford the sticker price, EVs offer new ways to support low- and middle-income consumers and communities.

How? Unlike most other DERs, EVs are mobile (and the most decentralized) by nature and can move rapidly to meet the needs of the grid. Charging times and locations can be shifted to modulate demand, and their batteries can push electricity back onto the grid when and where it’s needed most. This creative EV charge management is now made possible by advances in software informed by AI-powered flexibility management platforms.

But before their potential can shift into high gear, a fundamental problem needs solving: EVs are prohibitively expensive.

Solar Lit the Way to Expanded Access

Solar was once available only to a privileged few. Then governments, vendors and financiers developed new business models, such as tax incentives, leasing and related energy-as-a-service offerings. EVs can follow a similar path.

In 2022, the U.S. addressed energy equity head on with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), increasingly a global model for accelerating the energy transition. The federal law includes incentives of up to $4,000 for used EVs, an intervention geared to spur adoption across different income levels. Enrolling these used EVs in demand response programs could also open up new income opportunities across the board.

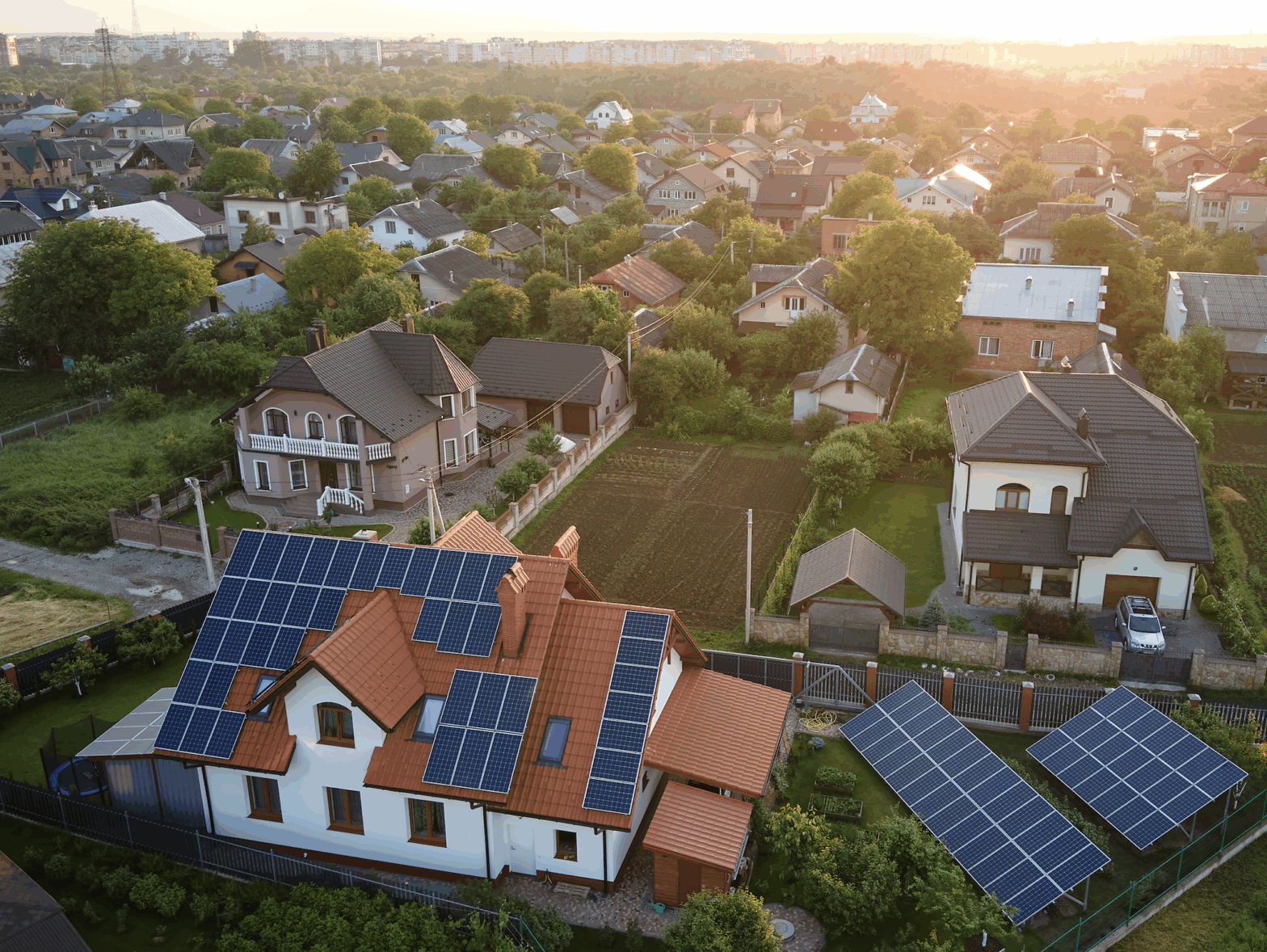

But the cost of a new or used EV is only one hurdle. Housing stock in lower income areas may not be battery-ready and is often rented, restricting residents’ ability to make changes. Also, the grid infrastructure supporting underserved communities may need upgrades, further limiting potential adoption since each EV represents the equivalent load of a new house on the distribution system.

The IRA is an excellent start, but in the spirit of solar’s “second act,” both public and private interests must develop creative approaches to break down barriers to EV adoption for all. For example, higher rebates and incentives for EVs could be offered at the state level for low and moderate income households.

In California, transportation is responsible for approximately 40% of carbon emissions. As a counter punch, a new law requires all passenger vehicles sold in California to be EVs by 2035. Thsi is great progress, but a report by the California Energy Commission estimates the state will need over 1 million new EV charging stations to support EV mandates designed to move the state from 1 million to 7.5 million EVs this decade.

To advance access and support equity, a portion of these EV chargers must be developed in underserved communities.

Car Ownership to Community Empowerment

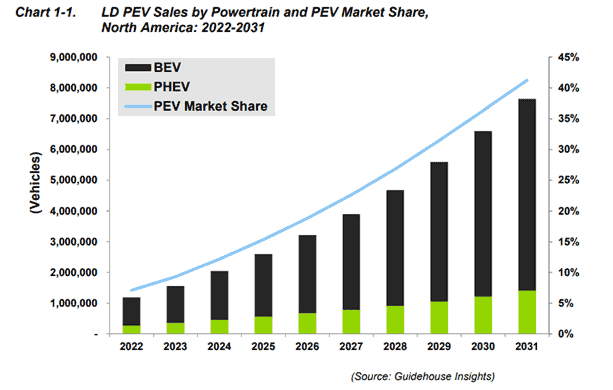

The growth in EV adoption is not limited to California, according to a 2021 report by Guidehouse Insights. And these projections likely underestimate future growth spurred by recent legislation.

As barriers to individual ownership fall and penetration rises, how can we mobilize EVs to benefit all communities and the grid? A cutting-edge pilot project and the emerging concept of mobile resiliency assets provide a promising roadmap.

Everyone suffers when the climate crisis causes power outages through droughts, extreme weather, and wildfires, but some vulnerable populations suffer more. Underserved communities, for example, may have access to no backup power supplies or only to fossil fuel-burning alternatives that exacerbate public health and environmental impacts.

But here’s a convenient truth: EVs are batteries on wheels. As such, they can become a back-up power source for community centers, shelters and other critical facilities. Regardless of ownership (individuals or private and public fleets), EVs can converge to back-up an entire building.

For example, Schneider Electric is working with the Oakland Public Library and AC Transit to use electric bus batteries as a storage asset integrated into a microgrid capable of keeping electricity flowing during grid outages. This way, a neighborhood library can become a fully-powered safe haven for surrounding communities during a crisis.

From Gridlock to Grid Support

Multiple pilot projects are exploring the use of EV batteries for microgrids and virtual power plants (VPPs) in South Korea, Denmark, and parts of the U.S., including at military bases. Fleets of electric buses can make grids more reliable and resilient with their larger batteries. And because they usually operate on set schedules, buses offer a more predictable grid resource.

Mobilizing EVs to support underserved communities during emergencies is just a first step. We need both short- and long-term solutions focused on environmental justice and equity. The Oakland pilot and similar projects can pave the way for other creative solutions with the help of public and private sector incentives and innovative technologies.

The bottom line? Equity cannot take a back seat to other urgencies of the climate crisis and energy transition. This would be both unacceptable and unwise.